About two years ago (in 2011, that is) I caught interest in autonomous / selfdriving cars*, when writing up a Thought Leadership piece with one of my PA colleagues. At the time, most (except transport nerds like myself) found it too science fiction like, despite Google had just started their trials at that time.

Nevertheless, discussions started to emerge on time frames, obstacles and implications. For example we had a good discussion in the LinkedIn ITS group on whether we would see driverless vehicles before or only after 2030:

Later on we also had a discussion in Denmark, on the site of the engineering society (Danish). Some argued it would never happen, whereas I argued (Danish) it would happen in 3 stages:

Later on we also had a discussion in Denmark, on the site of the engineering society (Danish). Some argued it would never happen, whereas I argued (Danish) it would happen in 3 stages:

- Driver-assist systems: Parking, platooning, etc. This we are seeing on the roads by now.

- Self-driving, with manual: Google-like, where the car drives, but you can overrule. This is coming soon.

- Fully automated, no manual: No steering wheel and pedals. Only computer driven. This will take time.

(Since then, the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has introduced a somewhat similar 5-level classification.)

However, during 2012 the concept of driverless cars has become mainstream:

Consequently, people are now more and more discussing not ‘if’ but ‘when’. And discussions emerge on whether selfdriving (electric) cars will be universally good, or whether they will just make it possible to pack even more cars onto the roads, kill public transport (buses, at least) and induce more sprawl:

Of course, there are also the speculations on how people will hack cars, and – more to the humorous side – how to have fun with them, a la the ‘cow tipping’ in the Cars movie.

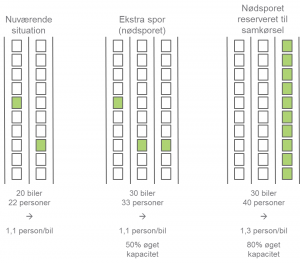

Let me for a while zoom in on the positive implications (fewer cars and parking spaces, due to computer managed automatic car- and ride-sharing) from driverless cars. In an inspiring study “Transforming Personal Mobility” from the Earth Institute at Columbia University, the output of simulations of a fully driverless car fleet is reported. The researchers investigate 3 cases: Ann Arbor, Babcock Ranch (a new development for 50,000 people) and Manhattan.

Although the models still needs refinement (does e.g. not yet take into consideration that origin and destination are usually not evenly distributed), it is still worth to note some striking conclusions made from the simulations:

- Ann Arbor: A shared, driverless vehicle fleet can provide the same mobility as personnally owned vehicles at far less cost (80% less for a driving need of 10,000 miles/year) (page 15)

- Babcock Ranch: Only 4,000 shared vehicles would be needed to serve the 50,000 people, with a waiting time well under a minute (page 19)

- Manhattan: A fleet of 9,000 vehicles could replace the 13,000+ yellow cabs, at only 10-15% of the cost (page 25)

- In all cases, add to this the reduced costs for parking and the time not spent driving.

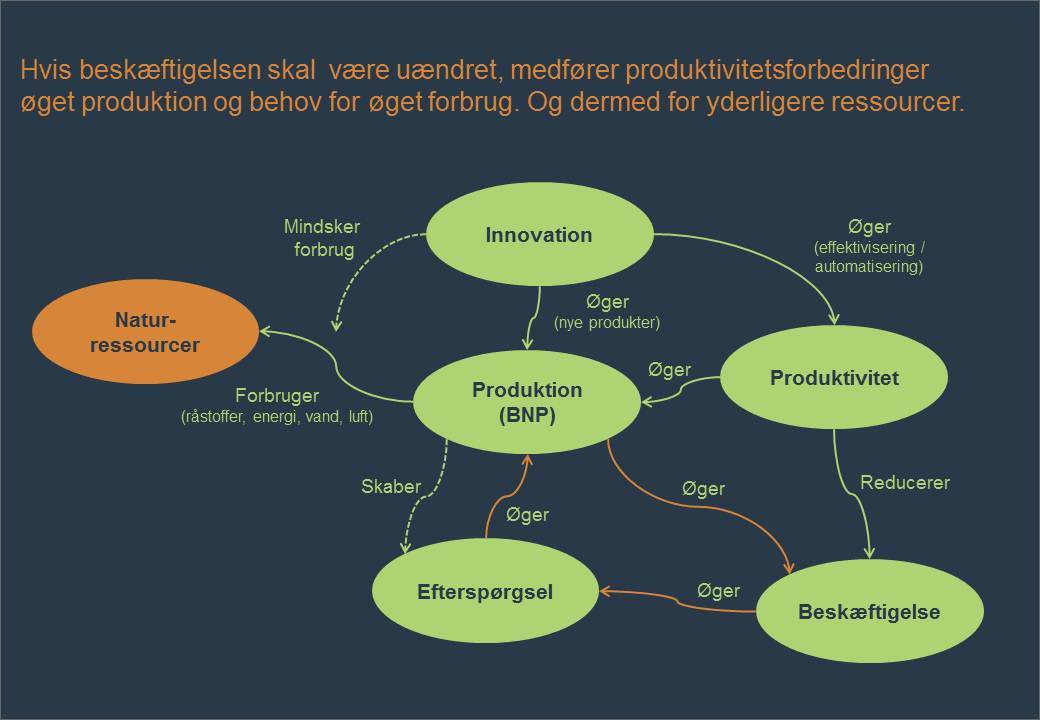

It is thus clear, that benefits would be enormous. Whether in the form of freed up space or additional traffic through the same infrastructure. But some will also be adversely affected, e.g. taxi drivers as we saw in the Manhattan example. Rather than technology, I actually that will be the main challenge – too many vested interests:

- Car manufacturers: Unless transport needs increase dramatically, much fewer cars would be needed

- Insurance companies: Less accidents would (should) mean lower insurance fee, thus lower revenues

- Cities: Less need for parking will remove a significant money stream from parking fees/fines

- Public transport: Heavy competition – suddenly the ‘time is your own’, also in the car; buses will disappear

- Government: Fewer cars means less sales tax

- Taxi firms/drivers: Will in most cases be made redundant.

So, nobody really wants to push the driverless cars forward. Except for Google. They have no vested interests in the current business, and has the potential to disrupt it completely. And while there are other firms/labs (e.g. Mobileye) developing equipment for driverless cars, it is likely that Google will end up with a large portion of the expected revenue in this future market.

Currently Google is allowed to experiment with one of the legacy manufacturer’s cars, the Toyota Prius. At some point (when the threat gets more real) Google may be met with ‘improper use’ litigation. But I don’t think it will stop them. They’ll probably only then join forces with Tesla, as some has speculated. Now, that would be cool. For customers. Less to for the ‘old’ auto makers.

So. Many benefits (type to depend on government policies), and potentially quite a few losers when the driverless cars takes the wheel.

—

*: While I here have focused on cars, there are similar developments in relation to driverless trucks for freight (particularly long-haul) and postal services. And much of the above also applies to trucks, with the addition that truck drivers’ unions may be a strong force against the introduction of driverless trucks.

Later on we also had a discussion in Denmark,

Later on we also had a discussion in Denmark,